Around 1 in every 123 people in the UK have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a range of disorders which involve chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, with prevalence increasing to 1 in every 67 people aged over 70. The most prevalent IBDs are known as ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease.

IBD can cause debilitating gut symptoms, including severe diarrhoea, bloating, abdominal pain, and blood in stools. It can also drive health issues beyond the gut, ranging from weight loss and nutritional deficiencies to joint pain and depression. Effective management of IBD is essential to improving an individual’s quality of life and minimising their risk of long-term complications. Research suggests that the microbiome may play a role in both the development and continuation of IBD, and dietary interventions to modulate it are showing promise for support alongside conventional treatments.

DIAGNOSING IBD

Testing for the protein, calprotectin, in stool is a helpful screening tool for identifying gut inflammation. If the levels are high, this can facilitate further internal investigations to distinguish IBD from other conditions which cause similar abdominal symptoms, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), coeliac disease, endometriosis, and ovarian cancer. The amount of hidden blood in the stool, known as occult blood or ‘FIT’, is also a helpful screening tool which can trigger further investigations for IBD or bowel cancer.

THE ROLE OF THE HUMAN MICROBIOME IN IBD

Once an IBD diagnosis and the necessary medical care is in place, it can be helpful to take a step back and look beyond the diagnosis.

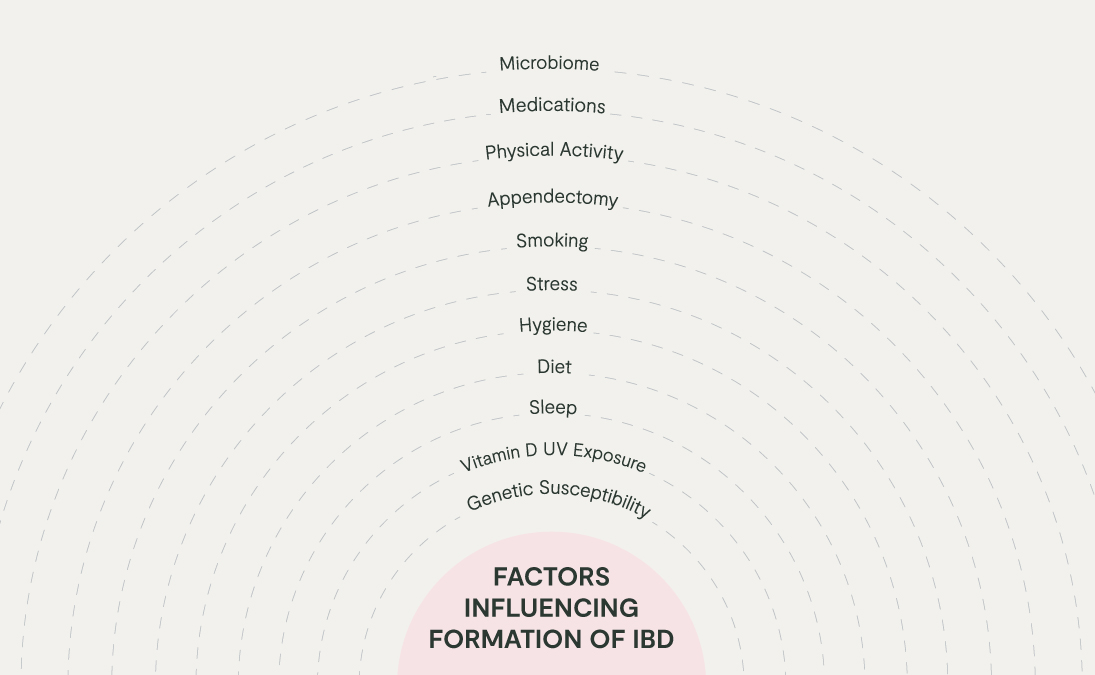

Taking into account the person as a whole and their life up until the point of diagnosis can unravel the combination of genetic, environmental, and immune factors which may have led to the development of their IBD in the first place. Factors influencing the pathophysiology of IBD include genetic susceptibility, sleep, and stress levels, vitamin D status, smoking, diet, and microbiome disruption.

One of the key patterns of imbalance associated with IBD is disruption to the colonies of microbes living within the digestive tract, which is sometimes termed ‘gut dysbiosis’. Given the stressors of modern life, gut dysbiosis can develop following high exposure to factors which disrupt the human microbiome, such as antibiotics, pesticides, low fibre intake, alcohol, and high stress.

The gut dysbiosis identified in IBD can involve an overgrowth of pathogenic (disease-causing microbes) or pathobiont (commensals which become pathogenic in specific circumstances) microbes, not least because they can cause an excessive amount of inflammatory ‘traffic’ in the gut. These may include the bacteria Clostridium difficile, the fungi Malassezia restricta, and hydrogen sulphide-producing bacteria such as Desulfovibrio spp..

Bacteria from the oral microbiome may also play a role. High levels of Fusobacterium nucleatum in the gut, a bacteria from the mouth which can drive gum disease, has been linked to the progression of IBD.

Dysbiosis in IBD is often associated with a ‘missing microbe’ picture too. This can be characterised by a low diversity and abundance of protective commensal bacteria, especially those which produce anti-inflammatory compounds called short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate or acetate, including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia homini, and Bifidobacterium spp.. Butyrate, for example, helps the gut wall to repair itself and to modulate inflammation. If intestinal butyrate production is low, the gut wall may become hyperpermeable and chronically inflamed through the loss of this microbiome-mediated healing mechanism.

The gut microbiome can further drive gut barrier dysfunction when colonies of ‘mucin-degrading’ bacteria start to overgrow, usually when there is a low fibre intake. If you think about the gut wall as an iced cake, the epithelial barrier is the sponge and the icing is the mucus layer. A thick, plump intestinal mucus layer cushions and protects the gut wall from the contents of the gut lumen.

When mucin-degrading bacteria such as Ruminococcus gnavus and -torques, overgrow, the mucus layer may start to thin, with the gut wall becoming more exposed to pro-inflammatory signals from gut microbes. When this scenario becomes chronic, aberrant inflammatory responses in the gut wall risk becoming the norm, potentially contributing to the gut wall damage seen in IBD. Chronic inflammation can conversely perpetuate gut dysbiosis and gut barrier dysfunction, creating a vicious cycle.

PERSONALISED MICROBIOME SUPPORT FOR IBD

1. Microbiome testing

Private stool testing for those diagnosed with IBD, guided by a healthcare provider (HCP), can be a useful gateway to personalised support. It can identify which patterns of host-microbiome disruption are relevant for each individual with IBD, enabling safe, effective, and personalised dietary and lifestyle interventions. Given the complexity of IBD, being guided by an HCP is recommended to help you navigate this complexity and receive the tailored support you deserve. It is also possible to assess the oral microbiome to gauge how oral health might be contributing to poor gut health.

2. Reduce exposure to stressors

Reduce exposure to stressors of the commensal gut microbiota and gut barrier, especially high stress, pesticides, preservatives, alcohol, and a highly processed, high animal fat, low fibre typical Western diet, while increasing your exposure to nourishing microbiome influences, such as:

3. Fibre

Ample consumption of a wide diversity of fibre (soluble and insoluble) is the cornerstone of ensuring a healthy commensal gut microbiome and increasing intestinal SCFA production. Aim for at least 30 different types of plant each week.

Be mindful to only make slow dietary changes to allow your gut time to adjust. You may also need to give some thought as to how you time such changes relative to any recent IBD flares. Given the complexity, ideally be guided by a HCP.

4. Polyphenols

From rightly coloured plants such as pomegranate, aronia berry, and citrus peel. Polyphenols can have prebiotic properties, support a healthy mucosal barrier in the gut, and modulate inflammation.

IN SUMMARY

Investigating the microbiome provides an individual with the opportunity to better understand one of the potential underlying drivers of their IBD, which can help empower them to make simple beneficial changes to their diet and lifestyle. Such a root cause approach, ideally guided by a suitably qualified HCP, can help individuals to better manage their IBD alongside conventional care and have a transformative impact on their lives.