Our mental health is inexplicably tied to our physical health and wellness. When we feel better, we have more capability to participate in life more fully and engage in situations that further support our mental well-being. For many years, mental health was thought to be only a problem of the mind, and not linked to the processes and functioning of the body that houses the mind. It has been known for many years that people that suffer from mental health conditions also suffer from other physical symptoms, such as gut symptoms often labelled IBS, but with little heed of what the connection may be.

Thankfully, change is upon us. An integrative model of mental healthcare which recognises the interconnectedness of our mind, body, and environment is gathering pace and on track to supersede the antiquated view that the ‘mind’ is distinct and separate from the body. Research into nutrition, lifestyle, and social and environmental factors is starting to gather pace and give us more tools to support our mental health.

One aspect of this emerging paradigm is the recognition that the microbes living within our gut can have an impact on our mood, for better or worse, and interventions to nurture the gut microbiome can be another supportive tool alongside exercise, social interaction, lifestyle advice, therapy, medications, and support

That Gut Feeling

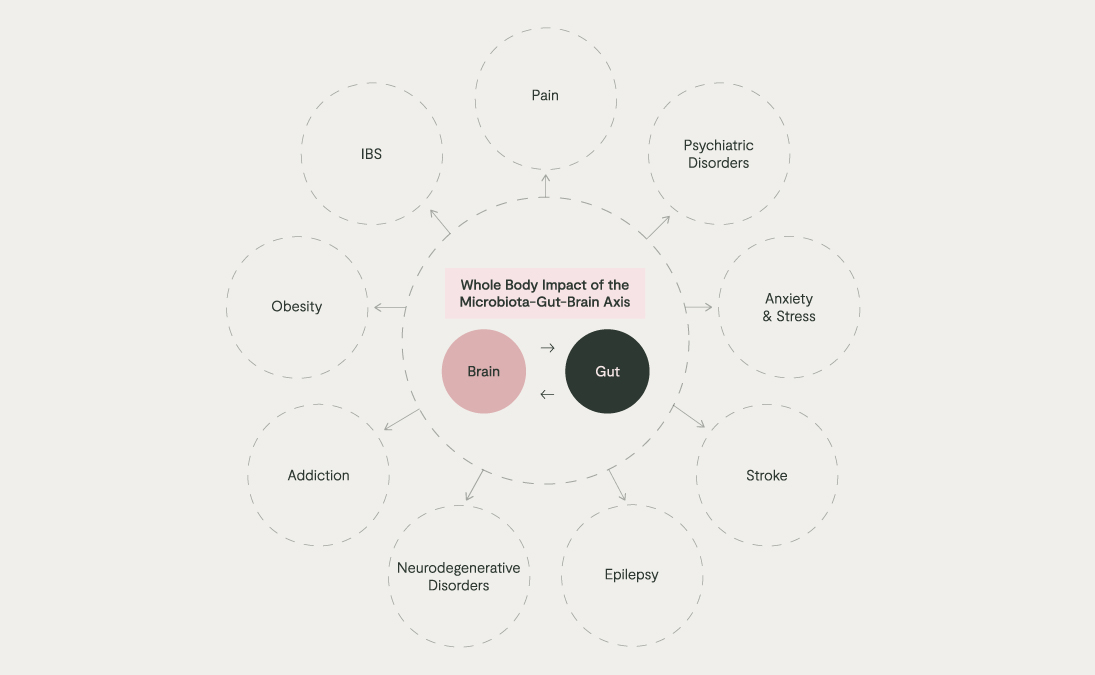

Nausea, constipation, diarrhoea, and a feeling of ‘butterflies’ in the stomach are symptoms which we have probably all experienced when we feel stressed. This is the ‘gut-brain axis’ in action, a term which recognises the impact of emotions on gut health and vice versa. We have known about this for a long time, from early recognition that irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is common in those with psychiatric diagnoses.

The function of the gut-brain axis has long been attributed to communication between different branches of the nervous system, especially the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord; CNS) and enteric nervous system (ENS), a subdivision of the autonomic nervous system comprised of the complex mesh of neurons surrounding the gut. These neural plexuses are in constant communication, feeding information back and forth – gut to the brain, brain to gut – as part of a sophisticated system which allows the brain to constantly survey what is happening around the body and adjust our physiology accordingly.

We have since come to learn that the gut microbiota helps to regulate the gut-brain axis. A landmark study showed that faecal microbiota transplants from depressed individuals into germ-free rats (those raised without a microbiota) induced depressive-like symptoms in the animals. More recent research has identified marked differences in the gut microbiome composition of individuals with psychiatric diagnoses.

The recently coined term, ‘microbiota-gut-brain axis’ should come as no surprise when we consider the evolutionary context. Humans have never existed without microbes and there has never been a time when the human brain has not received signals from microbes, especially those living in our gut. They can alter our behaviour and physiology, including immunity and mood, and we can alter them, for example, our diet and stress levels. Disrupted communication along this axis has, in turn, been linked to many health issues, ranging from anxiety, psychiatric disorders, and addiction to obesity and IBS.

The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Our Internal Microbial Internet

We are only at the beginning of our understanding of how the microbiota-gut-brain axis works, but some key themes are emerging.

Our gut microbiota is in constant, bidirectional conversation with the enteric nervous system, and immune system, which in turn impacts changes the signals in our brain

The nervous system is perhaps the best understood. Our understanding focuses on the role of the vagus nerve, the longest cranial nerve which connects the gut, cardiovascular system, and respiratory tract with the brain. The vagus nerve communicates many important messages from the brain to body, but it also transmits information from the rest of the body, including the gut, back to the brain. Around 80% of vagus nerve fibres bring signals from the body, back to the brain, which highlights just how much information the brain receives via this ‘bottom-up’ communication, including from the gut.

To help the vagus nerve fulfil its role as a sophisticated sensing system, vagal nerve fibres in the gut carry a vast variety of receptors, each of which can detect a different type of signal, including mechanical stretch, gut hormones, and substances produced by microbes. The community of microbes living in the gut affects which microbial metabolites are produced, in what amount, and this can be detected by the vagus nerve which can then send signals back to the brain.

Certain gut bacteria, such as Campylobacter jejuni, can induce anxiety-like behaviour by activating vagus nerve receptors in the gut with the metabolites they produce. Meanwhile, key commensal bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium can send calming, safety signals back to the brain. In fact, animal studies have shown that surgery to sever the vagus nerve, a vagotomy, can block their mood-modifying benefits.

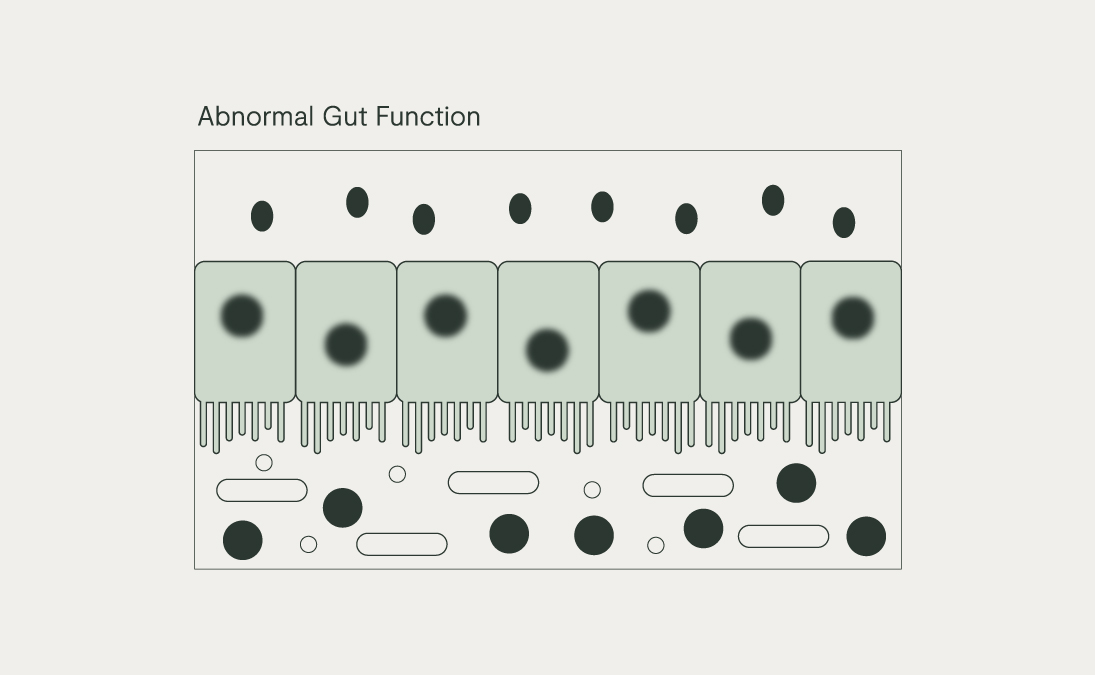

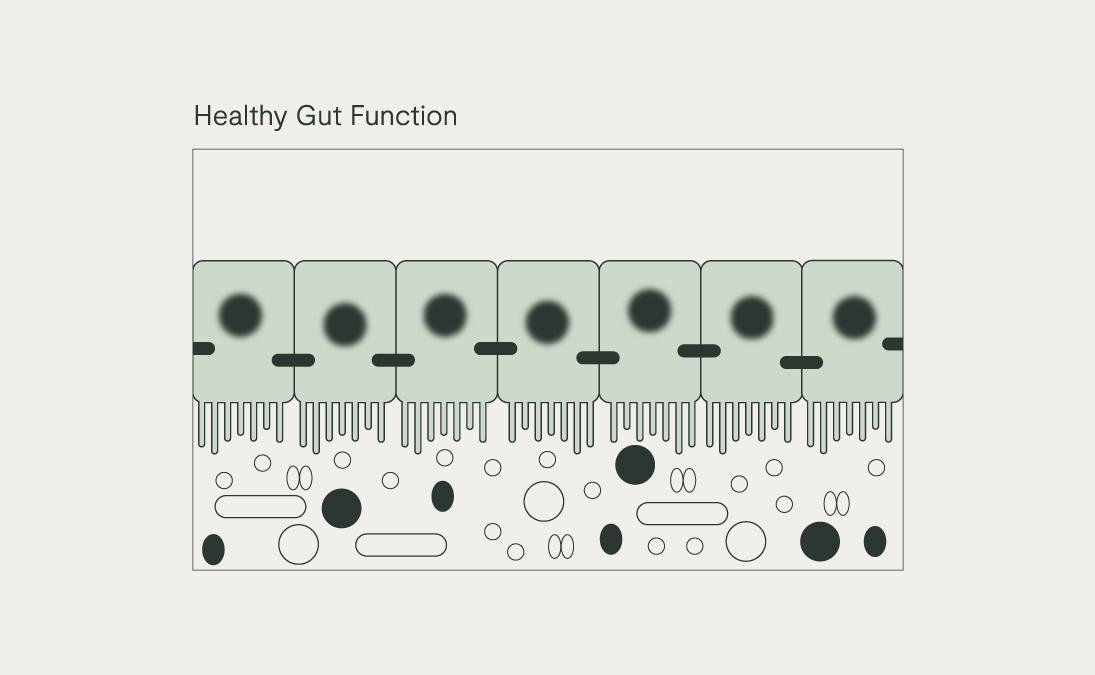

The immune system is another route of communication between the gut and the brain. The gut is a major route of exposure to the environment, especially through the food and drink that we consume. So, another way that the body surveys the level of safety in the gut is through the action of toll-like receptors (TLRs) on the gut wall which sense which microbes are present.

A diversity of commensal bacteria in the gut is detected by TLRs and sends ‘all is well’ signals from the gut to the immune and nervous system. Meanwhile, other bacteria can carry molecules on their outer cell wall called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) carried by Gram-negative bacteria like E. coli and Prevotella copri. These are recognised by TLRs as possible ‘danger’ signals.

An over-abundance of Gram-negative bacteria, coupled with an impaired intestinal mucus layer and epithelial barrier (e.g. low fibre diet, high alcohol intake), can drive an excessive amount of local immune activation. This can become systemic when the LPS is absorbed into circulation, driving a state called metabolic endotoxaemia. Some proinflammatory cytokines can then cross the blood-brain barrier and go on to affect mood and behaviour as part of the ‘cytokine-induced sickness behaviour’ hypothesis.

We have all observed how we become reclusive, fatigued, and apathetic when we have an infection. This depressive-like sickness behaviour during an inflammatory response is meant to be an acute scenario to promote healing when fighting infection. However, when the inflammatory signalling comes from a range of various sources, including gut dysbiosis and poor gut barrier health, crosses the blood-brain barrier and goes unresolved, it can lead to an ‘inflamed mind’ and chronic changes in mood and behaviour which resemble depression. Inflammation coming from dysbiosis in the mouth, as in gum disease, has also been linked with the risk of depression.

Microbial metabolites, such as neurotransmitters and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), can have a modulatory impact on these communication highways. Much discussion surrounds the ability of the gut microbiota to make neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). In fact, around 90% of the body’s serotonin is made in the gut. These gut-microbiota-derived neurotransmitters may not get to the brain in substantial amounts as they are made and broken down quite quickly in the gut, but studies have shown that they indirectly modulate our mood and behaviour by stimulating the vagus nerve.

In fact, SCFAs seem to influence our own production of neurotransmitters by increasing the expression of key enzymes involved in their production, such as those which make serotonin and dopamine. The anti-inflammatory impact of SCFAs might be another mechanism by which they can help soothe an otherwise inflamed mind.

Personalised Microbiome Support for Mood

One study which brought to light the promise of nutrition for mental health was the SMILES clinical trial conducted by Professor Felice Jacka. This 12-week controlled clinical trial found that an affordable, Mediterranean-style diet packed with fruit and vegetables, pulses and legumes, wholegrains, nuts, fish, poultry, and olive oil led to significant reductions in the depression symptoms of those with moderate to severe depression.

This new field of ‘nutritional psychiatry’ is gathering pace and an important subdivision of it is exploring how the gut microbiome might mediate the ability of diet to impact mood.

When thinking about how to start modulating the microbiota-gut-brain axis in daily life with a good chance of seeing a benefit, it can be helpful to nurture both sides of this axis at the same time:

‘Bottom-up’ support

1. Microbiome testing

Private stool testing, guided by a healthcare provider (HCP), is the ideal gateway to personalised support for your microbiome-gut-brain axis alongside other key nutrient testing such as vitamin D, folate, B12, and omega-3. It can elucidate the nature and degree of disruption to the commensal microbiota, including key species such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, and whether an individual has any of the specific commensal patterns which have been identified in those with mental health and psychiatric disorders, notably a reduced abundance of the butyrate-producers Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus. This information can then pave the way for tailored dietary and supplemental advice.

2. Food & Fibre

A high fibre diet rich in a wide diversity of wholegrains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes, specific prebiotic fibres such as partially hydrolysed guar gum (PHGG) and resistant starch, polyphenols (e.g., those from cacao, citrus bioflavonoids), and fermented foods (e.g. raw sauerkraut, kimchi, kombucha) can all help to increase the abundance of these butyrate-producers and generally improve the all-important gut-microbial diversity.

One recent study found that consumption of 30g 85% dark chocolate daily for 3 weeks improved mood parameters and that this was associated with corresponding improvement in gut microbiome composition, including the relative abundance of Blautia obeum.

3. Prebiotics

Specific prebiotics have been shown to support the relative abundance of key commensals such as Bifidobacterium spp. while providing a tangible benefit for mental health. For example, 3-weeks of galactoligosaccharide (GOS) supplementation has been shown to reduce salivary levels of the stress hormone, cortisol.

4. Live Bacteria (Commonly referred to as Probiotics)

Specific strains of live bacteria can also confer a psychological benefit, termed psychobiotics, including:

- Lactobacillus helveticus Rosell®-52 (R0052) and Bifidobacterium longum Rosell® -175 (R0175) – 3-week supplementation reduced gastrointestinal abdominal pain and nausea/vomiting in volunteers with stress-induced symptoms and a 30-day intervention reduced anxiety- and depression-related behaviours in human volunteers. The latter study showed a reduction in free urinary cortisol and improved levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a molecule which supports mental and cognitive health.

- Bifidobacterium bifidum Rosell®-71 (R0071) – 6-week supplementation increased the proportion of healthy days and significantly decreased self-reported stress scores in stressed students.

- L. plantarum Rosell® -1012 (R1012) – shown to reduce abdominal pain in IBS in clinical trials, with promising research in murine models showing potential benefit for the gut-brain axis.

This strain combination can be found in our best-seller Bio.Me Mind + Mood, alongside biotin to support the nervous system and psychological function

A practical benefit of prebiotics and probiotics for supporting emotional wellbeing is their suitability alongside psychiatric medications, unlike many other supplements, although this is best checked by the healthcare provider on a case-by-case basis.

‘Top-down’ support

While working directly on the gut microbiome and overall gut health, it is also helpful to complement this with nutritional and lifestyle interventions to directly calm the mind as these, in turn, help to further nurture the gut microbiome, gut barrier, and the inflammatory status of the body. These can range from deep nasal breathing, meditation, improved sleep hygiene, and nature therapy (e.g. forest-bathing) to an increased intake of nutrients and herbs such as lemon balm, saffron, L-theanine, and ashwagandha. These lifestyle and environment interventions can all work well alongside therapy, support groups and conventional medication

The beauty of modulating the microbiome-gut-brain axis is its ability to empower each of us with an understanding of the nutritional and lifestyle changes which we can all implement on a daily basis to support our emotional wellbeing from a whole-body perspective. After all, a healthy body supports a healthy mind, and a healthy mind supports a healthy body.